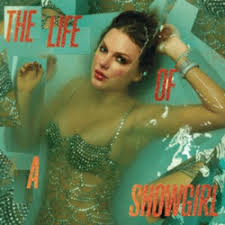

Of course I’ve been listening to Taylor Swift’s new record. Anyone who knows me knows that as I’ve been grading (it is midterm, y’all), I’ve been listening. And what I’ve been hearing is a lot of noise about TS’s lyrical weakness. Some of this, it seems, is being linked to Swift’s personal life. In a masterful journalistic dodge, Tyler Foggatt claims to be reporting “some of the most virulent and sexist anti-Swift discourse in years,” when he titles his article for the New Yorker, “Do We Still Like Taylor Swift When She’s Happy?”[1] What I thought when Foggatt’s ironizing piece ended up in my inbox is that Swift knows what she’s doing in beginning her new album, Life of a Showgirl, with a meditation on Ophelia.

Swift’s Ophelia is not, thankfully, the adolescent girl crushed by cultural expectations then recuperated by self-help culture.[2] Instead, she is “The eldest daughter of a nobleman/ Ophelia lived in fantasy /But love was a cold bed full of scorpions / The venom stole her sanity.”[3] She is betrayed by love, by the expectation that she define herself in relation to a man who uses her openness to center himself as he struggles for recognition on a larger stage.

In this Swift is true to Shakespeare’s character. When Swift vows, “I swore my loyalty to me, myself and I,” she limns her thinking about Ophelia with strength, with toughness, with endurance. Ophelia is not fragile or fraught, overwhelmed or overcome. In seeking to avoid the “fate of Ophelia,” Swift sings about the happiness she finds in a lover who sees her as worthy of attention, respect, and pursuit. She is relieved to find a different love, “And if you’d never come for me / I might’ve lingered in purgatory.” This does not make her weak; nor does it render Ophelia as fragile, passive, disposable, or discarded. Instead, it suggests Ophelia might have been happy, might have loved again, had she been allowed to do more than see herself through the unfeeling eyes of a man who uses her affection to advance his own drama.

In thinking about Swift’s Ophelia, I recalled my own reaction to Shakespeare’s character in The Matter of Virtue (2019). There I interpreted Ophelia as enacting an embodied ethical practice of world (re)making. Rather than summarizing my argument, I thought I’d just recycle myself, as my argument about Shakespeare’s Ophelia is unchanged:

Ophelia is moved to madness by her former suitor’s violence and disregard. But her break with reason, critics have observed, is not without rhyme. Ophelia’s songs are popular street ballads. Putting such songs in the mouth of a madwoman, Mary Ellen Lamb points out, means that Shakespeare has erected a binary of elite/popular, male/female to establish Hamlet’s superiority…The content of the ballads Ophelia performs, however, invests her grief with a different kind of virtue. A betrayed lover’s song, a dirge for a dead beloved, and a ballad of a maiden’s downfall: through these songs, Ophelia delineates a visceral awareness of the harms she has suffered, so that her performance gives her dignity even as she becomes a spectacle of tragedy. Caralyn Bialo observes that Ophelia’s songs allow her to inhabit female subject positions usually placed off-limits for elite women, such as herself. Ophelia bodies forth the voices of sexually aware, socially expendable women…Ophelia does not go quietly. Rather, her physical immediacy critiques the social and ethical failures that have led to her madness. Hamlet’s vengeance, though he might choreograph it to catch the conscience of Claudius, also entails Ophelia’s reckless and heedless destruction…Laertes then Hamlet may jump into Ophelia’s grave, but their theatrical mourning is simply part of the public masculine contest they wage against one another. When Ophelia makes herself visible—as broken, disheveled, and discarded—she uncovers a material virtue that stands in direct opposition to the public posturing of Hamlet then Laertes. Unlike Hamlet’s madness, which is donned for social advantage, Ophelia’s madness is a scandal that subjects the court’s values to critical scrutiny. When Gertrude reports Ophelia’s death, she paints a picture of a faithful maiden whose drowning was precipitated by her lover’s desertion. While attempting to hang garlands of flowers on a willow, as abandoned lovers were proverbially said to do during this period, a branch breaks and Ophelia is drowned in the tangled weight of her garments. If her madness prevents her from preserving herself, her death also indicts Hamlet’s use of Ophelia as an expendable prop in the revenge tragedy he plots against Claudius. (30-32)[4]

In singing about Ophelia, Swift gives new voice to the idea that she might have lived, loved, and thrived. It is perhaps easier to see Shakespeare’s destroyed beloved as forever in stasis, as the famous painting by John Everett Millais suggests.[5] She is suspended in her own death, a sacrificial supplicant whose beauty is permanently preserved. In Swift’s reckoning, she sees herself as lucky: “You dug me out of my grave and /Saved my heart from the fate Ophelia.” What happens if we imagine Ophelia as surviving, as living beyond her lover’s abuse, as loving another who values and pursues her affection? Do we like her? Or would we prefer to see her suffer?

When Swift announced her engagement a few weeks ago, I thought it was notable that she foregrounded her gifts as a lyricist, identifying herself as “Your English teacher” (not “Your music teacher”) when she looked forward to marrying “your gym teacher,” Travis Kelce.[6] After listening to the songs where Swift’s new love takes cultural shape, I’d say she was doing some sophisticated thinking about the changed potential of Shakespeare’s character. To affirm her own happiness, Swift honors Ophelia, adding a new song to an old story, one that suggests women can sing a different tune about love, happiness, survival, and endurance.

[1] Tyler Foggatt, “Do We Still Like Taylor Swift When She’s Happy?” critics notebook, The New Yorker, October 5, 2025: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/critics-notebook/do-we-still-like-taylor-swift-when-shes-happy.

[2] Mary Pipher, Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls (Random House, 1994); Cheryl Dellasega, Surviving Ophelia: Mothers Share Their Wisdom in Navigating the Tumultuous Teenage Years (Random House, 2001).

[3] Taylor Swift, The Life of a Showgirl, Republic Records, 2025. All quotations from “The Fate of Ophelia.”

[4] Holly A. Crocker, The Matter of Virtue: Women’s Ethical Action from Chaucer to Shakespeare (Penn, 2019). Footnotes in the original are not included.

[5] John Everett Millais, “Ophelia,” 1851-52, Tate Britain.

[6] Instagram, August 26, 2025: “Your English teacher and your gym teacher are getting married.”